The circular economy idea is out there. In the past ten years, it’s gone from being a niche idea to an undeniable trend. Many are captivated by the potential for change in the way they live, work, or innovate. And many more are feeling the urgent need for a circular economy, as the ‘burning platform’ moves from metaphor to real life. So whether through passion or necessity, the idea isn’t going away – it’s the end of the beginning.

Spurred on by this wave of interest and expectation, many businesses are setting ambitions, targets, and strategies to move from linear to circular. This direction setting is an important step in the journey to make the circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. a reality.

The transition means doing things differently – and that’s happening too. People are rolling up their sleeves, grappling with the concept, and working to put it into practice.

You’ve probably noticed an increase in taglines like “Wear Sneakers Ltd now makes trainers out of 12% recycled material!” around products on shelves and in press releases or media coverage, emphasising how a company is taking some resources they previously viewed as waste and using a few of them to create something new. This use of waste, along with a lot of other types of innovation, is often categorised as ‘circular’. The fact that these stories are becoming more visible is evidence that we are taking the first steps away from the wasteful, linear economylinear economyAn economy in which finite resources are extracted to make products that are used - generally not to their full potential - and then thrown away ('take-make-waste').. That is good news.

However, I have a confession to make. Sometimes when I see examples like this under the banner of a circular economy, I feel disappointed. I get judgemental. I turn into a circular snob.

What happened to the big, beautiful vision of a circular economy? The vision of a future in which we have redesigned everything so waste has been eliminated in the first place rather than cleaned up.

Where we make convenient, useful products that improve people’s lives, valuing and circulating them, at their best, for as long as possible. And, where we regenerate our natural systems so they are thriving and abundant.

These principles – eliminate, circulate, regenerate – challenge the very fundamentals of our current, linear economic model. So why is the term being used to sell a product that contains a bit of recycled material?

Increasingly, it feels like the public and the media have this reaction too. They say ‘nope!’ or ‘we don’t believe you’ or ‘look at the other stuff your company does’ or ‘it’s not really that circular, is it?’ or ‘ok, so you recycled it once, but what happens after that?’

As someone who says those types of things, in doing so, I feel like I’m honouring the severity of the global challenges that we face, and hence the scale and ambition of the solutions we need to meet them. On top of that, I believe I’m protecting the purity of that big, beautiful vision by sticking to what the theory says.

But what if there’s another consequence of this response?

I put myself in the shoes of the person or people behind the product. The people that achieved that ’12% recycled material’ milestone.

I imagine those people had good intentions when they worked on this project.

I imagine them sitting in a meeting with their boss, figuring out how they were going to hit their KPI around reducing material waste.

I imagine they were proud of what they’d accomplished.

I imagine them testing the product with users or customers, or seeing some media coverage, and getting a positive response that made them feel good.

I imagine that what they did felt hard. They had to work with people they’d never worked with before, with some unfamiliar technologies and processes.

I imagine them thinking how this project rekindled their design school idealism.

And lastly, I imagine that they learnt from this project and that it revealed things they will do differently next time, should they get the chance. In fact, they know the things that their colleagues, suppliers, or customers could do differently to make their job easier.

I’ve spoken to many creatives, designers, and innovators about the circular economy over the past 10 years. Most of the people who have helped make our linear world are excited about the opportunity to reinvent it – to play their part in the shift to a circular economy.

So when I think about the designers or innovators trying to accelerate this transition, I understand why they’re proud of their achievement, even if it is a small step towards a circular economy rather than a great leap.

Some efforts are more circular than others

If you zoom out across time and space, it’s pretty safe to assume that most of the innovation we need to create a circular economy has not been realised. The economy is still linear, after all. So there’s a lot of work to be done. I think it’s important that we distinguish between different mindsets and stages on the journey to a circular economy.

People are experimenting, which is essential. Innovating for a truly circular economy is a process, and each innovation takes us a step closer. But not all attempts at circular design are created equal. I think we undermine the idea of a circular economy itself if we don’t get more serious about the pathways of thinking and implementation that will get us there.

Sure, there are some small and large businesses taking those profound systemic leaps towards a circular economy. But a lot of progress isn’t like that.

Some efforts are well-intentioned, incremental steps towards the circular economy. People ‘get’ the circular economy. They understand the full picture – that big, beautiful vision. They’re on the right track. But their ideas aren’t finished – and they know that they might never be finished. The transformation of our economy from extractive and linear to circular and regenerative is a systemic, ongoing mission. Evolving with continuous feedback is a core part of circular design.

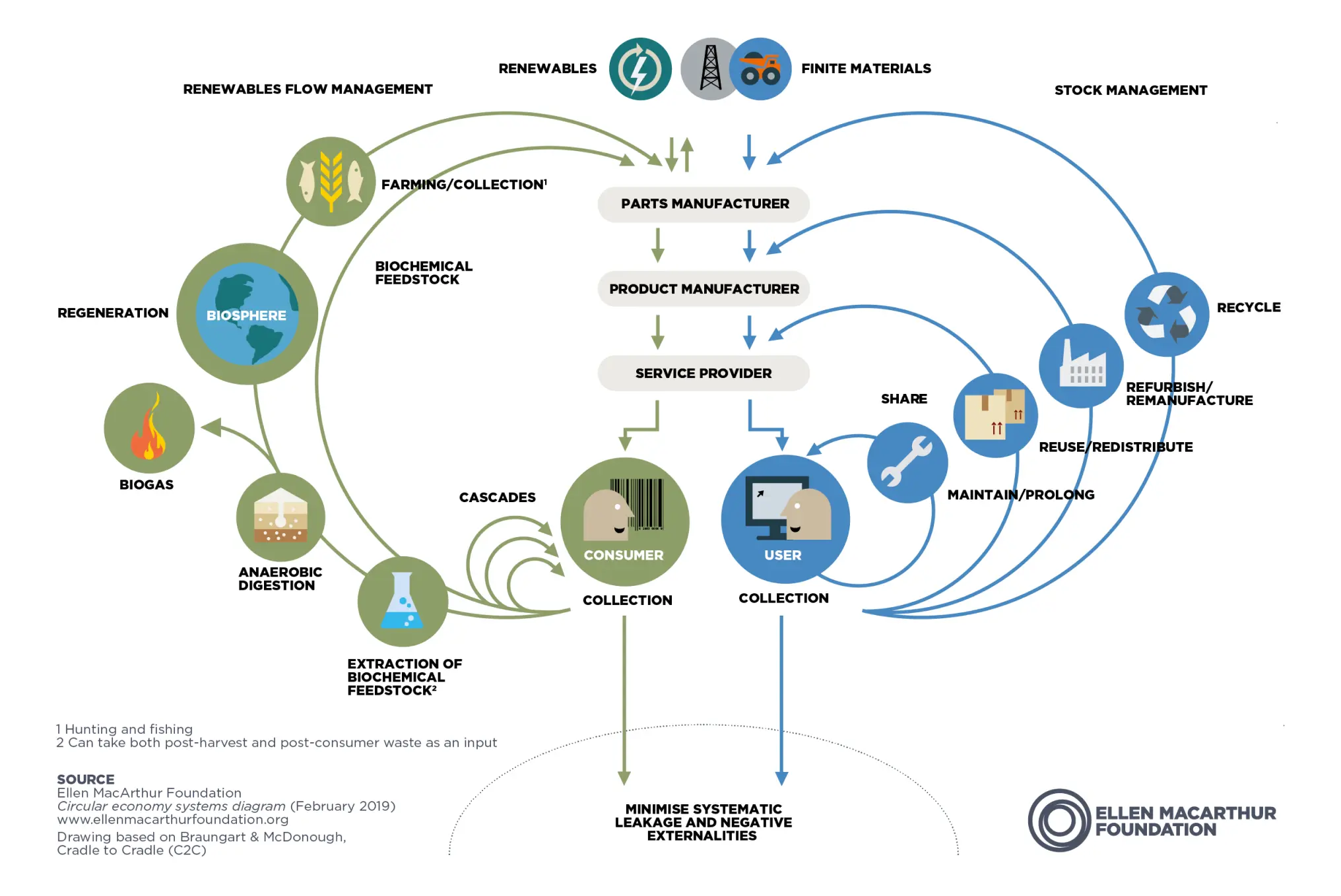

Then there’s innovation from folks like Wear Sneakers Ltd, our helpful fictional brand mentioned at the top of the article. They also have good intentions, but aren’t entirely clear of what the circular economy is, the direction they should be heading, or the steps to get there. For instance, they might be saying to themselves “let’s reduce the impact of manufacturing each product, scale our recycling, and then we’ll look at re-use.” The circular economy model offers a hierarchy of strategies as we move from the outer to inner loops: from remanufacturing to repairrepairOperation by which a faulty or broken product or component is returned back to a usable state to fulfil its intended use., reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification., maintenance, and sharingsharingThe use of a product by multiple users. It is a practice that retains the highest value of a product by extending its use period., we increasingly preserve the integrity, the embedded energy, and labour of the product itself. So the main issue with their approach is that recycling should be the last option, not the first – it’s the inner loops of a circular economy that should be the aim.

The second connected issue is that designing for a circular economy often doesn’t follow such a simple path. Designing for material efficiency alone, for example, might involve decisions about lightweighting, materials selection, or manufacturing processes that are contrary to activities like reuse, repair, or remanufacturing. Those decisions might make a product less durable or harder to repair. To follow the priorities of our fictional company, addressing recycling next might then not be a stepping stone to reuse. It might even take you in a different direction entirely.

Circular design requires a systemic approach, stepping back to take a wider view before putting strategies in place.

There’s another collection of businesses that are full of good intentions, but short on such commitment. They might have tried something out, such as an isolated product or line, or a short-term pilot. It felt good, it looked good, but they haven’t much intention of scaling or replicating it, changing the wider business, or shifting their industry.

And then there are a few businesses with bad intentions. They might be talking about some sort of ‘circular economy’, but they’re deliberately going in the wrong direction, because of vested interests in the linear economy. Let’s not worry too much about them now. As industrialist W. Edwards Deming is said to have quipped, “survival is not mandatory”.

So if the circular economy is a serious idea – and thankfully many believe it is – then I think we should recognise these differences, and acknowledge that some circular economy efforts are more circular than others.

The journey to a circular economy

Taking this notion a step further, we should acknowledge different starting points and collectively support each other to change the way we think about the circular economy transition, from ‘get it done’ to ‘get started and keep going’.

Now that the circular economy idea is out there, you might have an image in your head of moving from linear to circular. There’s a transition that needs to happen, and it needs to happen fast. That gives the impression of getting from point A to point B. But what does the journey look like? I think we know it doesn’t look like a straight line.

It’s much more like the ‘design squiggle’ by Damien Newman. A cliche, but a good one. It’s often used as a shorthand for the process that sits behind new innovations. But I think we can use it on a meta scale, to reflect the challenges of transitioning to a circular economy.

The Process of Design Squiggle by Damien Newman, thedesignsquiggle.com

This line represents a journey. It’s a tangled mess of progress and setbacks, experimental dead ends, flashes of inspiration that fell flat, and dogged determination that eventually paid off.

While on the wiggly path, an innovator might be a long way from that big picture vision of a circular economy that they read about on a website, in which nothing is wasted. But, even so, they tried.

They’re playing their part in moving towards a circular economy.

How do we encourage creatives on this turbulent journey to keep going? How do we prevent them from feeling discouraged by failures and setbacks? How can we nurture passion in exploring possibilities, rather than seeing circular economy as simply a compliance exercise, or an administrative chore?

Perhaps we can have a conversation about circular economy design and innovation that embraces getting it almost right, or taking steps towards the big beautiful vision of a circular economy without undermining that vision. Rather than saying 'you got it wrong', we could say 'good start, you’re on the right track, but keep going – there’s more to this circular economy idea’.

Perhaps we need to have a different conversation about circular economy innovation. One that is more honest, in which we reinforce what is directionally sound, celebrate those who have the courage to innovate, and support and stretch our peers at different stages of their journey.

This might sound trivial or a bit soft. But I believe that message of ‘we’ve started, we have a way to go but we’re committed to getting there’ is a message that resonates with the public, employees, suppliers and throughout industries.

This mindset is the context that can make all our individual efforts make sense. The circular economy transition becomes less about the flashy pilots or one off-innovations and instead becomes an approach that unites people, that is bigger than one person, bigger than one department. A journey that the whole organisation is on.

I’ve got a term for this attitude. I call it ‘circular-ish’.

Circular-ish is the bit in the middle. It’s the stage we’re at now – where things get real. It’s where we translate the circular economy from premise to pragmatism.

Circular-ish is an attitude or posture, one that reflects the dynamic nature of this transition. It’s a commitment you make to yourself, your colleagues, and to society, that means “we’ve started, we’re trying, and we’re committed to doing better”.

Circular-ish isn’t a technical term. It’s not an excuse for bad design. If you’re thinking ‘Great! I can do the bare minimum’, shrug your shoulders and say ‘don’t hate me, it’s circular-ish!’, then I’ve missed the mark. And I say to you, you can do better. Embrace the state of circular-ish, and learn to love the messy reality of circular economy innovation.