Good COP, bad COP: What makes a good climate change conference?

The world has pinned its hopes on the fact that this year’s global climate conference, COP26, will deliver the action-conducive consensus that is urgently needed to address climate change. But what is the COP, who are the actors behind it, and what can we expect from this year’s edition?

These days, it seems like not a day goes by without news of yet another country, company, city or another institution committing to ambitious climate targets in a bid to keep the rise in global temperature below 1.5 degrees. A key impetus behind the flurry of climate-focused activity this year is the much-anticipated COP26. Scheduled to take place from 1-12 November, this edition of the Conference of Parties (COP) is expected to deliver a concrete pathway for the world to move from statements to action when it comes to the Paris Agreement. Momentum has been building since the previous COP took place in Madrid in November 2019, so the stakes are high.

This edition of the COP comes six years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, whereby the majority of the world’s nations committed to containing global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5 degrees. It is therefore a key moment to take stock of progress, but also ramp up commitments together with a clear action plan of how the targets will be met in the short, medium and long terms.

But what does this event need to deliver for it to be deemed a ‘good’ COP? Who are the actors behind it? And what do the many acronyms frequently used in climate diplomacy — COP, UNFCCC, IPCC, BINGO, RINGO, ENGO — actually mean?

How it all started

The year was 1992 and the future seemed full of promise. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the end of the Cold War that had effectively divided the world into two blocs for over four decades. While many rejoiced in their newfound freedoms, borders opened, and trade barriers were lifted, the UN convened the largest global gathering to discuss economic development and the environment, held in Rio de Janeiro.

In June 1992, the result of more than two years’ worth of diplomatic efforts resulted in the UN Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED), better known as the Earth Summit, which convened some 30,000 representatives of 178 governments, NGOs, media, and other interested parties in the Brazilian metropolis. Among the documents that resulted from the summit were three that have stood the test of time: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD), and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). The governments of the countries that signed these legally binding conventions became parties to the respective conventions and began to meet regularly to discuss progress at so-called Conferences of Parties on climate, biodiversity, and desertification.

The COPs were born.

Rio de Janeiro hosted over 30,000 representatives of governments and civil society to discuss economic development and the environment at the Earth Summit in June 1992.

With 197 signatories as of 2015, the UNFCCC has since become the best known of the three conventions, though the secretariats of the other two have also continued to work with their respective signatories on global action to protect biodiversity and combat desertification, respectively.

Starting with COP 1 in Berlin in 1995, the UNFCCC Secretariat has been convening its signatories yearly at what has become the world’s largest climate event. Over the years, in addition to climate diplomats and national delegations, the event has become a source of attraction for many civil society groups, artists, journalists, business representatives, academics, and others. So much so, that recent editions of the COP have attracted as many as 40,000 participants from all over the world.

Who’s who at the climate COPs?

The 197 national delegations are organised into five regional groups: African States, Asian States, Eastern European States, Latin American and Caribbean States, and the Western European and Other States. Yet the substantive interests of parties are not represented at the negotiations in this regional format. Rather, national delegations have organised themselves in smaller groups over the years that better reflect their interests. Among these groups are the Arab States, the Least Developed Countries, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) group, the G77 group of developing countries, AILAC (Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean), the EU27 negotiating bloc representing EU member states, and the BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, China, India). And we’re just getting started with the acronyms.

National delegates gather at the COPs every year to discuss progress on climate action. Picture by United Nations Climate Change on flickr

Civil society action hub at COP24. Photo by Claire Miranda / APMDD

Aside from the national delegations, which have the greatest level of influence over negotiations, a number of international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other actors are allowed to observe the process. Since the number of observers that can attend different sessions is often capped, these organisations are also grouped into constituencies that can send representatives to follow the negotiations. Some of the most influential observer groups at the COP are the ENGOs (environmental NGOs), the RINGOs (research and independent NGOs), the LGMAs (local governments and municipal authorities), TUNGOs (trade unions), and YOUNGOs (youth organisations). Business and industry also have their group and opportunity to shine at the COP during the BINGO Day.

Recounting his past experience as an observer, Tim Gore, a COP veteran who currently leads the climate change programme at the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP), said:

‘The currency at these events is access to information — understanding who has access to what information or access to the latest texts to identify opportunities to put proposals on the table. For observers, access is difficult to secure, because the negotiations will often take place in smaller groups and/or in informal settings that don’t appear on the official agenda, making them difficult to track. Even for official negotiations, oftentimes the only way for observers to gain access to information is to wait outside the closed doors behind which the discussions take place until delegates come out, hoping that they’ll share some details with them as they walk to their next meetings.”

While they might not be invited to the negotiations among specific groups, observers are, however, allowed to attend the plenary sessions, which are the biggest gatherings at the COPs. The plenaries are generally expository and not very eventful, though a few notable exceptions have happened in the decades-long history of the event. For instance, a memorable incident took place at COP 15 in Copenhagen, when the Danish hosts ignored calls for a point of order from Claudia Salerno, Venezuela’s lead negotiator at the time. After repeatedly slamming her hand against the table to attract the attention of the hosts, Salerno put her bloody palm up with a rhetoric demand:

“Do you think a sovereign country has to actually cut its hand and draw blood? [..] This hand, which is bleeding now, wants to speak, and it has the same right of any of those which you call a representative group of leaders.”

Tim Gore explains: “The two weeks during which the COP takes place every year are incredibly intense for delegates, who get little sleep and are often involved in back-to-back negotiations. This occasionally results in emotional reactions when negotiations break down.”

Aside from being an observer, another way for non-state actors to be involved in climate diplomacy is through the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action, which was set up in 2016 to strengthen and accelerate climate action among parties and non-parties to the UNFCCC. Rather than invite its thousands of members to observe the negotiations, the platform enables them to collaboratively shape the vision for a climate-neutral and resilient future, which is expressed in the form of documents called Climate Action Pathways.

There are two Climate Action Champions that oversee the initiative for every edition of the COP and that are appointed by the host countries. They act as a bridge between the Marrakech Partnership and the UNFCCC Secretariat, helping the latter to mobilise action, convene technical expert meetings, and coordinate annual high-level events. Among the events that they organise every year is the Global Climate Action Hub which takes place at the COP itself.

What will make COP26 a good COP?

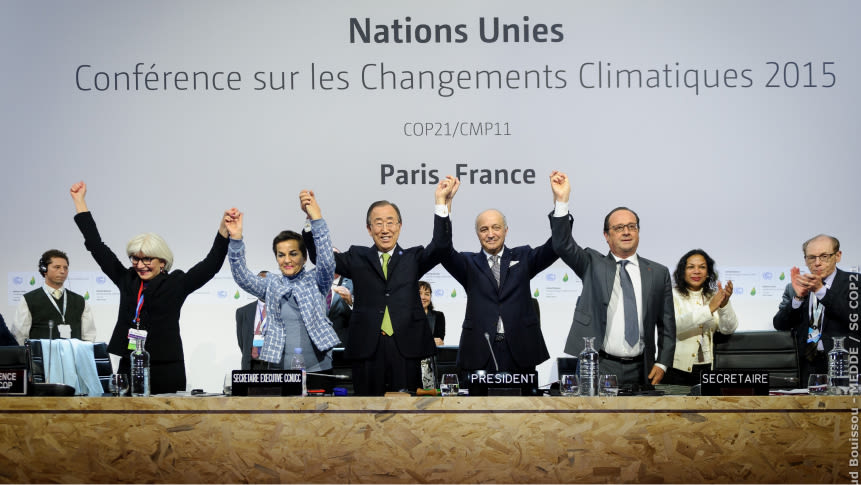

The Paris Agreement, adopted at COP 21 in 2015, was the culmination of more than two decades’ worth of climate diplomacy work. Holding hands on the stage at the final plenary session, the French hosts, Christiana Figueres, then-Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC, and Ban Ki-moon, then-UN Secretary General, were beaming.

“[The Paris Agreement] is an agreement of conviction. It is an agreement of solidarity with the most vulnerable. It is an agreement of long-term vision, because it is an agreement of commitment to turn this new, legal framework into the engine of safe growth for all for the rest of this century,” Figueres concluded enthusiastically.

Difficult as it may have been to reach the Paris Agreement, the hard work had only just begun — containing climate change at well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably at 1.5 degrees, as the Paris Agreement stipulates, is no easy feat.

Moving from words to action has proven to be tricky and to take time. In the six years since the agreement was adopted, its 197 signatories have made differing levels of progress on addressing climate change. More than 190 countries have developed and published at least one version of their national action plans, also called nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Yet the level of ambition in these NDCs needs to be raised. Existing national plans put us on a path to a global warming of more than 3 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

As the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the departure of the United States from the Paris Agreement in 2019 affected its standing in climate diplomacy and the global community’s overall ability to address climate change. Since the country rejoined the agreement earlier this year, there is now renewed focus and momentum. Today marks an important milestone in the US’ renewed commitment, as it has announced its first NDC under the Paris Agreement at a summit of global leaders convened by the White House.

Since urgent action is necessary to mitigate climate change, there is pressure on governments from all over the world, and particularly on the world’s biggest emitters, to move beyond commitments to net zero emissions by a distant deadline like 2050. The pressure is mounting for them to take urgent action and make significant progress on reducing emissions this decade. By setting an emissions reduction target of at least 50% by 2030, compared to 2005, the US is taking a meaningful first step in regaining its place in global climate diplomacy after its four-year hiatus. However, even that target would mean that the country’s per capita emissions in 2030 would be higher compared to the European Union’s per capita emissions today.

To progress on the commitments set out in the Paris Agreement, the UK, which will host COP26 this November and therefore holds its presidency, has set an ambitious set of goals for the event in consultation with the UNFCCC parties. Foremost among these goals is the need to finalise the so-called ‘Paris Rulebook’, which sets out how countries will go about implementing the Paris Agreement. Countries have a significant amount of discretion to define their national climate plans; the rulebook sets out requirements on information, transparency, the global stocktake process, and the implementation and compliance mechanisms. Most of the rules have been agreed upon, though some outstanding issues, such as the rules on carbon markets, remain. Finalising the rules before the Paris Agreement enters into force later this year is crucial.

In addition, the UK Presidency of COP26 has set out the following goals for the event:

Ensuring mitigation efforts are stepped up — that is, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions —in order for the 1.5 degree Celsius temperature goal to remain within reach;

Strengthening adaptation and resilience to protect us, and particularly the most regions of the world, from the impacts of climate change that we can’t avoid;

Mobilising the USD 100 billion in climate finance that developed countries have endeavoured, in the Paris Agreement, to allocate every year to support the decarbonisation of their developing counterparts. The UNFCCC is based on the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibility, meaning that the entire global community needs to partake in the efforts to combat climate change, but that those efforts need to be commensurate with the capabilities of each signatory.

Underpinning the three goals above, the UK COP26 Presidency has set out to enhance international collaboration, particularly around the five themes of this year’s event, which are: clean energy, adaptation and resilience, energy transition in transport, nature-based solutions, and finance.

Underpinning the above goals are the broader issues of transparency, justice, and inclusivity, which have been ongoing moot points in the negotiations and which the UK Presidency of COP26 is committed to tackling head-on by convening the parties to online and in-person negotiations in the lead up to COP26.

Beyond the formal agenda, the COP is seen as a deadline for countries to announce their revised NDCs with more ambitious emissions reduction targets while, informally, the event is an opportunity to stock-take and discuss the progress towards meeting the Paris Agreement. For that reason, the event is seen as a global climate moment for a wide variety of actors and not just for the governments that participate directly in negotiations.

The circular economy and COP26

Depending on the source that generates them, greenhouse gas emissions can be tackled through different strategies. Some emissions, like those coming from petrol or diesel cars or from the generation of electricity, can be addressed through the transition to renewable energyrenewable energyEnergy derived from resources that are not depleted on timescales relevant to the economy, i.e. not geological timescales., by electrifying transport, and through energy efficiency measures in buildings and industry.

At the same time, some 45% of man-made greenhouse gas emissions come from how we produce and consume products and food; they come from industry, agriculture, and land use changes. They come from the use of fertilisers in agriculture, from the emissions released when forests are felled to make room for agriculture, from livestock rearing, from chemical processes in industry, and from the high-heat processes that underpin the manufacturing of many of our industrial products, among others.

Often called hard-to-abate emissions because of the difficulty in addressing them, they require an overhaul of our economy to be tackled at source. They require that we transition to a circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature., that we shift our diets to consume fewer animal products, and that we speed up the pace of technological innovation. To address them, we need to go upstream at the source of emissions to design waste and pollution out of our economy altogether, to keep materials in use, and to regenerate natural systems. To fulfil the Paris Agreement, particularly the ambitious goal of containing global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, we need to eliminate the hard-to-abate emissions; and, for that, we need to transition to a circular economy.

Yet few of the NDCs submitted by the UNFCCC signatories refer to the circular economy as one of the solutions that will deliver positive climate outcomes in their countries, according to Robert Bradley, Knowledge and Learning Director at the NDC Partnership. To date, much of the focus of climate strategies and activities, in both the private and public sectors, has been on changing our energy system, which is pivotal, yet insufficient if we are to contain global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Broadening the understanding of the solutions needed to contain catastrophic climate change and taking action on all the solutions that can meaningfully contribute to decarbonising our world is a matter of utmost urgency in the lead-up to COP26 and thereafter. Speaking at WCEF+climate, an event about the circular economy and its potential to contribute to climate action, in April 2021, Bradley noted that, nevertheless, many countries reference activities related to the circular economy in their NDCs indirectly.

For instance, Colombia’s recently published NDC features strong commitments towards reducing forest degradation and deforestation, which, in turn, requires a good management of materials. Chile is a notable exception. The most recent version of its NDC clearly connects the dots between the country’s climate targets and its transition to a circular economy and sets out three clear objectives to advance the latter within its borders.

Helpfully, Chile is not entirely alone in this and the global community is quickly awakening to the importance of a circular economy to tackling climate change. Speaking at WCEF+climate, Patricia Espinosa, the Executive Secretary of UNFCCC, concluded that ‘accelerating the shift to a circular economy is essential to achieve the climate goals agreed by the international community and to help rebuild the world’s economies stronger, greener, and better’. Dozens of government, international organisations, and civil society leaders from all over the world echoed her words, pledging, at the same event, to accelerate the transition to a circular economy as a tool for combating climate change.

One can only hope that these pledges will be reflected in the important plans, legislation, and negotiations that are being rolled out this year. Connecting the dots between the circular economy and climate change is imperative if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change.