In brief

When the Finnish government introduced a packaging tax on soft and alcoholic beverages, competing retailers and breweries united to create a shared logistics platform for returning empty bottles and cans nationwide. Their combined approach led to recovery rates of over 95%, making it one of the most effective deposit-refund systems (DRSs) in the world. This case study shows how direct competitors collectively unlocked scale to drive lasting market transformation.

The race against packaging waste

During the Helsinki 1952 Olympics, Coca-Cola introduced a local return system for its refillable glass bottles, which helped boost Finland’s growing interest in reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification.. But when single-use packaging eventually entered the beverage industry, excessive waste overwhelmed the country.

In 1983 the Finnish government introduced legislation that included a beverage packaging tax on non-reused or non-recycled soft and alcoholic drink packaging. The tax was designed to encourage environmentally responsible packaging as well as the use of deposit systems across Finland. Based on packaging volume, no tax was levied if the packaging was part of the deposit-based system, which remains the case today. The deposit return system was originally run by the state-owned company, Alko Oy, which had exclusive rights to sell alcoholic beverages stronger than mild alcohol, and also dictated the packaging requirements for alcoholic products.

However, when Finland joined the European Union in 1995, the regulatory power of Alko Oy came to an end, creating a need for alternative packaging types and DRSs. The private sector saw an opportunity to overcome this by working together, united by a shared goal to avoid or reduce taxes while providing alternative packaging solutions, such as aluminium cans.

PALPA – collaboration as an unlock

Six industry giants – including the three major retailers Alko Oy (owned by the Finnish government), Inex Partners Oy, and Kesko Oyi, and the three competing breweries Hartwall Ab, Olvi Oyj, and Sinebrychoff Supply Company Oy – joined forces in 1996 to form a separate nonprofit, named Suomen Palautuspakkaus Oy, or ‘Palpa’. Palpa’s goal was to develop an efficient and cost-effective DRS for beverage packaging, initially cans, but has grown to include glass and PET plastic.

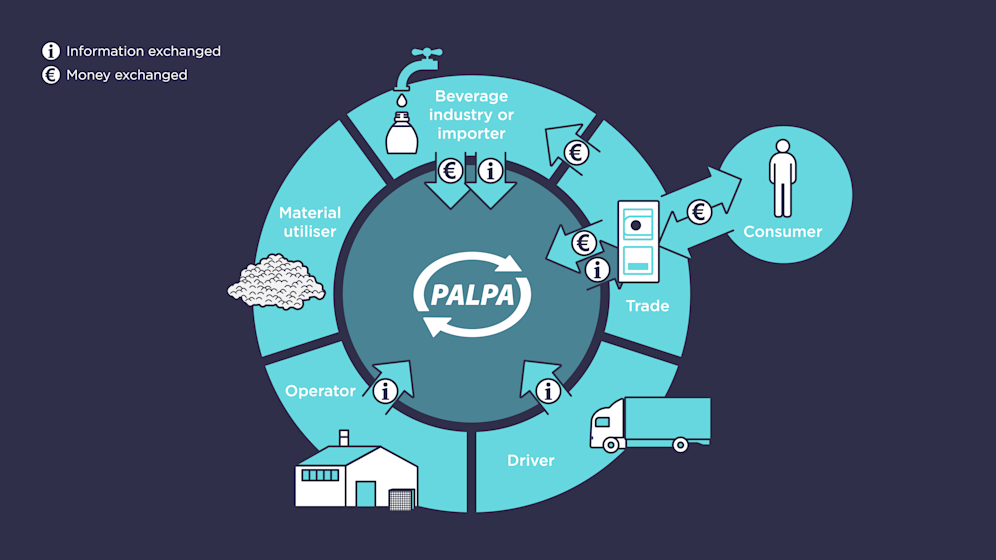

With just 15 employees and no operational assets of its own, such as reverse vending machines (RVMs) and recycling plants, Palpa now acts as a central coordinator. Instead of owning the operational equipment, the nonprofit outsources all operations and leverages Finland’s existing infrastructure for return, transport, and processing. The model is built as a DRS where the deposit circulates with the beverage package:

Purchase with a deposit: When a beverage is sold, a deposit (ranging from EUR 0.10 to 0.40 per container) is added to the price and passed from producer to retailer and ultimately to consumer.

Return and refund: Once the drink is consumed, customers can return the empty packaging at any authorised return point, such as grocery stores or service stations, using RVMs. These machines sort the containers on-site and issue a deposit refund to the customer. All businesses, including hotels and restaurants, that sell deposit-marked beverages must accept returns.

Collection and processing: The sorted bottles and cans are picked up by transporters contracted by Palpa and taken to centralised processing facilities, where contaminants are removed and materials are bulked for recyclers.

Recycling and reprocessing: After processing, the materials are sent to recyclers or beverage packaging manufacturers. Palpa’s recycling fees are tied to the material value rather than recyclabilityrecyclabilityThe ease with which a material can be recycled in practice and at scale., packaging made from materials with higher market value, such as aluminium, incurs a lower recycling fee. Palpa’s contractual conditions require the materials to be maintained at their highest value: for instance, aluminium cans should be reprocessed into new cans.

Reimbursement and reporting: Using data collected throughout this chain, Palpa reimburses the retail locations for the deposits, pays the transport and processing contractors for their services, and verifies and reports sales data to tax authorities.

While Palpa can view a participant’s production volumes, sales forecasts, and other sensitive data, competitors never can. Palpa aggregates data to create a level playing field for breweries and retailers. With these safeguards in place and equal decision-making power between both sectors, it has fostered and made faster implementation possible.

The same breweries and retailers that own Palpa also operate Ekopullo (Ekopulloyhdistys ry), a nonprofit that administers refillable beverage packaging, including secondary and tertiary packaging, under a DRS. In addition to supporting Palpa’s system, Ekopullo offers its own comprehensive reuse system for brown glass bottles, trays for PET and glass bottles, aluminium cans, and transport pallets and dollies.

Financing: Beverage companies fund all operations. Producers and importers pay membership and recycling fees, which cover logistics, processing, and handling costs. Palpa also earns revenue from selling high-quality recycled materials. Even the small amount of unclaimed deposits from unreturned containers is reinvested to improve the system.

Palpa is completely nonprofit and receives no government funding.

– Tommi Vihavainen, Palpa's director of producer services

A blueprint for developing critical logistics for a circular economy

With an annual turnover of around EUR 80 million and roughly EUR 360 million in deposit fees circulating each year, Palpa sits at the centre of one of the world’s most successful DRSs for beverage packaging. While favourable policy helped catalyse the initiative, it was the industry’s willingness to work together that scaled and sustained it. Palpa’s consistently high return rates – over 92% of PET bottles and 99% of aluminium cans and glass bottles are recovered – prove that commercial collaboration can transform markets on a national scale.

The model continues to work because everyone in the value chain benefits. Producers can pool resources to realise economies of scale, lowering per-unit recycling costs and making it more cost-effective than paying packaging taxes. Retailers earn handling fees and build customer loyalty through a straightforward, convenient return system. And customers are incentivised to participate by receiving a full deposit refund.

Even companies not subject to the beverage packaging tax – such as juice producers – are engaging with Palpa, driven by circularity goals and the desire to build customer trust through visible environmental action. As the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive mandates a 90% plastic bottle collection rate by 2029, governments and businesses are turning to Palpa to understand its approach. Sectors facing similar infrastructure challenges can look to it as a working example of how to collaborate with competitors and across sectors to build long-lasting, scalable systems.

Prompts for action

Who else depends on the same logistics or infrastructure and what would it take to plan and build it together?

What of your existing assets – like fleets, warehouses, or platforms – could be reimagined as a shared asset if combined with others who have similar needs?

How could aligning around common logistics or infrastructure needs help meet new regulations more efficiently, or unlock funding, policy support, or partnerships not accessible individually?