In today’s episode, we’re placing nature in the centre of the conversation. Joined by Sean Quinn, Director of Regenerative Design at HOK, we’re exploring the role of regenerative design in creating infrastructures that are in harmony with our communities and the planet and the importance of building technologies that restore natural systems instead of overpowering them. But we’re not stopping there, join us as we discover an exciting case study that uses regenerative design.

Do you want to know more about Building Prosperity, the Foundation’s report mentioned in this episode? Head to our Building Prosperity page to learn more.

If you enjoyed this episode, please leave us a review, or leave us a comment on Spotify or YouTube. Your support helps us to spread the word about the circular economy.

Listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcast.

Transcript

Colin Webster 00:03

Hello, and welcome to the circular economy show from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. My name is Colin Webster. I'm here today with me as my colleague, pepper scholly.

Pippa Shawley 00:11

Hi, Colin. So we know that the circular economy was not invented by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. It's a decades old idea. But it is inspired by some schools of thought. And that's what we're looking at in this series.

Colin Webster 00:22

Exactly right. This is a five part series on an each episode, we're looking at one of the schools of thought that inspired the circular economy. So there's Cradle to Cradle there's biomimicry, industrial ecology, there's a performance economy. And in this episode, we're going to take a closer look at regenerative design. And

Pippa Shawley 00:40

what I was really keen to do in this series is go beyond the theoretical side of this and actually look at the practical application of it. And I think you've found a really good guest for this episode

Colin Webster 00:49

on excellent guests who talks exactly about the practical applications of regenerative design, which I have to say, is the one I probably knew least about before I started digging in the CDs. And it might not be my favorite.

Pippa Shawley 01:01

Oh, okay, that's encouraging to hear. Yes.

Colin Webster 01:04

So our guest today is Sean Quinn, he is the director of regenerative design at H or K, who are a global architecture, engineering design and planning firm. I started this conversation by asking him to tell us what regenerative design actually as.

Sean Quinn 01:23

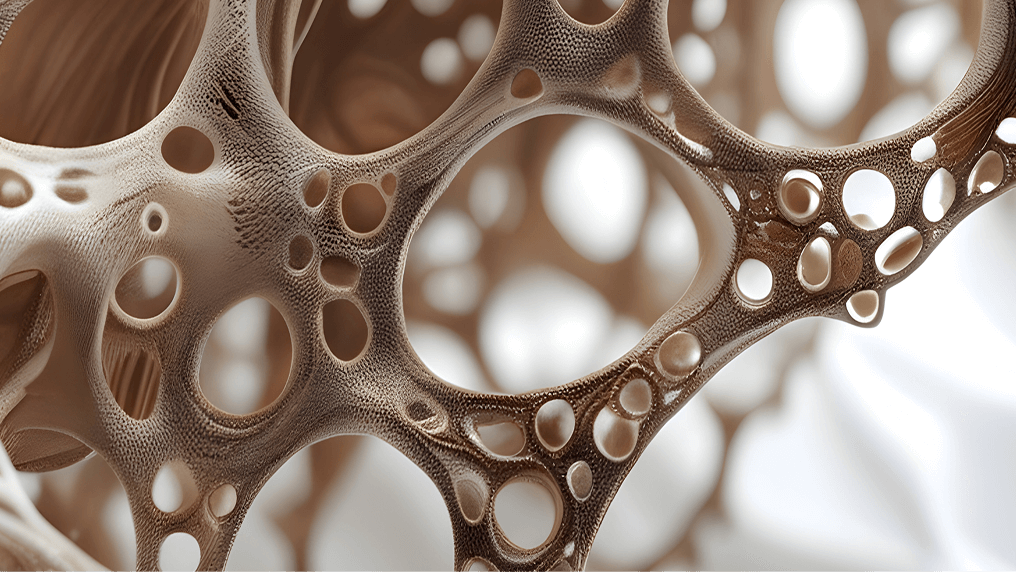

Yeah, so I mean, put it really simply, regenerative design is, is looking to enrich our communities and renew the earth. And so what that means is that over the course of the past 50 years or so we've seen development really look to leverage nature for its benefit. And as a result, we've seen a really degenerative impact. And so day to day, typical practice, really limits the ability to create any synergistic benefits long term. And so when we hear the sustainability mission is really based on a level of conservation, how can we limit the damage, mitigate harm, be more efficient in our resource consumption? When we talk about becoming carbon neutral, it's the goal of having zero impact that we're going to be able to generate as much energy as we consume, that we're going to be able to create structures that don't emit noxious emissions into the environment. Restorative design takes a first step in a different corner, it recognizes that we have depleted forms. And so how do we begin to actually reestablish natural systems in that place? Regenerative design, goes a step beyond that, and actually recognizes that development and nature could benefit from each other, and actually lend themselves towards a fully synergistic relationship. So regenerate designed to put it really specifically into a sort of a technical definition, enhances a site's ecosystem performance beyond the native habitat in a development and community where human and natural systems support each other, and eventually co evolve as one. And so as a result of being able to sort of tear out a parking lot, be able to bring nature back into the center of a development, we can create habitats to become more beneficial towards workplaces towards living towards play, and that the buildings that actually could potentially grow from that are being built out of life friendly materials that are more enhancing of the people inside of that, that actually as a result of both a nature friendly development process. And as a nature friendly building process, the environment around it starts to thrive. One of the key additional pieces to it is that we want to be inclusive to two communities, that the development can only benefit those that are able to afford it. And so what is the relationship that the community has to access that site or to benefit from the externalities that actually, that actually leave that site?

Pippa Shawley 03:56

Colin, he is speaking my language. This sounds great. The

Colin Webster 04:01

audio was good.

Pippa Shawley 04:01

I mean, the idea of it being affordable for everybody, the idea that it goes beyond sustainability beyond netzero, regenerative things that aren't just agriculture, it I tend to be allergic to the word synergy and synergistic. But it sounds quite appropriate here. I guess another term that we sometimes use is harmony.

Colin Webster 04:22

Yes, it excites me for all of those reasons to see I told you, it was my favorite one. One of the things I really enjoyed them talking about was bringing nature into the center of a development, which reminded me a little of a report that we're just about to publish called Building prosperity, which looks ideas exactly like that. How, how can we build with nature in harmony with nature and give people access to it, which I think is so important. And yes, then thinking about communities as well, people who could benefit from these sites, and all the schools of thought that we're talking about in the sea. is its regenerative design more than any other? Yes, absolutely more than any other that has a real focus on all of these different spheres, including the community itself. It really comes through strongly in regenerative design,

Pippa Shawley 05:15

I think that also ties in with the fact that economics is a social science. And maybe we don't always talk about the social side of it, and that we are part of a society. And whatever changes we need to make, we need to have everybody on board for the secular transition to happen.

Colin Webster 05:30

Yeah, there. There is a lot of talk in the circular economy, literature about health benefits, job benefits, which have all sorts of spin off additional benefits, too. But I guess the point I'm making about regenerative designers, it probably goes a little bit deeper than that, and involves the community and getting involved in decisions that go beyond some of those elements to should we have some more from Sean. Yes, let's do that. So we will go on to talk about the specifics of how regenerative design is applied. But we start this next segment, where I say to Sean, that this sounds a lot more complicated than maybe typical architecture,

Sean Quinn 06:04

it actually involves all of the same ingredients and elements that go into a normal building project. What's different about it, is the means by which we plan it. And that you're trying to actually have this very direct linear process, getting ourselves back into the sort of methodology of circular, circular design. So a owner or developer, as you said, going to create a specification for a project, I want a new office building to under 30,000 square feet to fit my growing company, I'm going to hire an architect who's going to hire an engineer, a landscape, and a landscape designer. And then eventually, that owner is also going to hire a contractor, they're going to plan, design, and execute that building. In separation through a series of meetings, they will, in an integrated fashion, begin to look at what each other is doing, and bounce back off of it. In a regenerative process, we really make that integrative process a little bit more we call trans. Disciplinary, they want to ensure that all of the decisions that are going into that process begin to lead towards the big, greater whole. And that's what we've initially got ourselves to be towards being able to accomplish we call it net zero energy buildings. When you combine the brilliance of architectural design to design more efficiently, you take engineering and more integrative fashion to look at the balance between architecture and engineering. And a thoughtful contractor is able to execute that through modular, modular manufacturing, sustainable construction methodologies, we can create a development that is more sustainable, or net zero energy. Regenerative design, now really tries to give a little more weight and heft and importance to the role that nature has to play in that. And so beyond just looking at building technologies, which is what we've typically looked at for the past 50 to 75 years of construction, we're trying to go back to the essence of how do we look at ecosystem services, the role that nature plays to improve soil health, which gives us a benefit, improved water quality, water, stormwater quantity management, and allows trees to grow in nature to thrive, which increases biodiversity. All of that creates the conditions for which it's better for human health and well being. And as those forests or micro forests or landscape systems begin to thrive, it gives us the additional benefit of carbon sequestration, which improves air quality. And so regenerative design takes that simple role that has at one point in history been really powerful the role of landscape to really ensure that we have a phenomenal place that surrounds a building, and instead says that landscape actually needs to take a more driving factor in this. And that rather than using using building technologies to sort of overpower the environment, we're actually going to leverage natural systems and utilize building technologies to help better manage those processes. And when there becomes an exchange between the artificial built environment and the natural environment, where we take the wastewater or buildings and funnel it in through its irrigation, where we take the heat, that's, that's lost over buildings and recapture that towards energy to supply other buildings around us, we begin to start seeing this sort of closed loop system form. And that's where you're trying to not only sort of use less, but actually extend the life of what we're doing the sort of second principle of the circular economy. So that third principle that arises to regenerate nature, that we can actually begin to have natural systems thrive as a result of that development being there in the first place. Again,

Colin Webster 09:43

I love the sound of everything you talk about. But I'm also hitting a skeptic, or imagining a skeptic would say, all this stuff sounds great, but it costs money. And why should my building develop? meant clean the air. Why should my building development give energy to neighboring buildings? Why should I be considering considering the health of the soil outside of my building?

Sean Quinn 10:12

Yeah, I'll give you one really great example, we can actually save you money in your development because you'll need to build less. If you can actually climatically tune those natural spaces outdoors, you can provide an amenity that creates a more, more valuable residential development because of the amenities that that you create outdoors. You can create a more flexible, adaptive and resilient workplaces by creating those spaces outdoors. So one phenomenal example from this is at Stanford University, where we developed out their new School of Medicine's center for academic medicine. It's here we looked at the Mediterranean systems we find in the west coast and really began to look at the coastal Live Oak evapo transpiration process actually cools the outdoor environment. And it does that by actually sequestering co2, breathing out oxygen, and pulling in water sources from below the soil that allows that space to become really adaptively. Cool. So by actually bringing an arboretum forest into our campus, rather than sitting the campus adjacent to it, were able to create a series of microclimates outdoors, which ensured that we had in the summertime a broad gateway that allowed wind to flow through and shade to fall on top of underneath that building, a winter garden where we actually use higher Sri heat absorbing materials to keep the keep the outdoor workplace warm. And at the edge of the building, we set forward outdoor balconies, workplaces, patios, where you are directly in the Arboretum, it stays kind of consistently in at about a 65 to 75 degree temperature for about eight months of the year. What that means, by placing actually 20% of the building program outdoors, we were able to actually demonstrate a methodology which we could shrink the building by 20%, and provide a more beneficial workplace. Now, the real key secret here for from the skeptic is who is going to want to leave their controlled office environment where everything is kept to a certain temperature, everything is kept to a specific humidity, you've got good electric lights, and you've got power supply, why would I leave that environment to go work outdoors. And the simple fundamental of that is that we actually feel better when we are outdoors. When we're moving when we're dynamic, our brains actually begin to function better. So those might be on a different neuro diversity spectrum. Some folks want to find a nice quiet place for sort of, you know, prospect and refuge. Other folks want to go into an environment where they can be a little more boisterous and sort of, you know, really play off of a dynamic environment around them, and consistently move. In that case of creating these different natural systems outdoors, we really create both of those benefits, the result of impact, what do we see the success of that story happened when the building opened during COVID. And so in 2021, when everyone was working remotely, as we are now here on this call, everyone coming to work with skeptical of going back to an interior environment, where the H vac system was controlled, where air was going to be recirculated. And so the vast majority of spaces were actually felt and enjoyed outdoors. And so folks really flocked to those spaces. And as we've moved now to three years later, and the building is at full capacity, the outdoor balconies are more populated than the directly neighboring enclosed conference rooms. Wow. So people would rather be outside looking over the trees, hearing the bird sounds, and having a collaborative meeting, like we're having right now than to sit into an enclosed conference room with electric lights with H vac buzzing around us. That environment is actually more comfortable.

Pippa Shawley 13:58

Listening to Shawn talk about how people tend to want to work outside and away from those air conditioning systems and see the trees really reminded me of something I learned about Charles Darwin when he was working on his theory of evolution was that he would go for walks twice a day and he would I think he called them like thinking pants or something like that. Because being in nature helped him process his thoughts. And I think that's a very interesting reflection from Sean that. To be surrounded by that kind of environment is really beneficial for our work.

Colin Webster 14:35

Yeah, actually, that is a big part of regenerative design. Shan Shan did tell me in this conversation, they call it Biophilia. Which is this idea that we benefit from this direct contact with nature of being surrounded by trees, the birds scene and so on. But, pepper you know, I live up in Edinburgh, where is not a Mediterranean environment a lot the time you don't want to

Pippa Shawley 14:58

be working on your balcony.

Colin Webster 15:00

Every day, even when it's nice weather, you can't see your screen in your laptop anyway. So very difficult. But um, so of course, the thing about regenerative design is that the designs are they're not cookie cutter, the designs are placed based adapted to local conditions. So

Pippa Shawley 15:17

if Shawn was building something up in Edinburgh, it wouldn't be the same thing that he's building in California. You mean? Yeah, that'd be

Colin Webster 15:23

ridiculous, wouldn't it? As we said, Here's a quote from the John Lyle, who's the big name I suppose in the world of regenerative design, he wrote a book, approximately the turn of the millennium there. And this encapsulates it well, he says, We're nature evolved an ever varying endlessly complex network of unique places adapted to local conditions. Humans have designed readily manageable uniformity. That sounds familiar.

Pippa Shawley 15:50

It does. Should we go back to your conversation with Sean,

Colin Webster 15:53

that's cool. There must be key principles to regenerative design, and I'm guessing, working with the local environment, not just working with it, but helping to regenerate it must be must be right up there. Which, which implies thinking and systems must be a key part of regenerative design to

Sean Quinn 16:17

ya know, the number one focus within regenerative design, it is a holistic Systems Thinking methodology. You're trying to create value for all stakeholders to give new life or energy to something that has been depleted, and to generate net positive impacts for the community, it's going to inhabit that site for for the environment and for the community around it. And so that holistic systems process begins by identifying the local contexts and conditions of place tender site. And one of the things that's become really interesting as our abilities now to quantify the sort of baseline performance of the natural, the natural ecosystem, so we often partner with a group called the Eco metric Solutions Group, as well as biomimicry 3.8 eco metric Solutions Group is able to actually through decades of sort of onsite research into the different criteria parameters of the landscape, identify what ecosystem services nature provides in a healthy environment, and also in the target site being a brownfield and urban infill or, or a Greenfield. And then through our collaboration with biomimicry, it's really looking at the key characteristics of a biome. What are the keystone species, the flora and fauna that have evolved and adapted to the challenges and you find and in cold and foggy Scotland, to the Mediterranean, California to sort of hot and humid Middle East. And it's once we begin to identify that delta, that performance gap that exists between the baseline of the site that we find in the healthy habitat that neighbors, we can begin to create strategies that close that gap. And so regenerative design really looks to implement strategies that move us towards positive performance.

Colin Webster 18:12

Tell us where did this idea of regenerative design come from them?

Sean Quinn 18:18

Yeah, so it actually originates in permaculture. So it's really in the 1970s in Tasmania, that we sort of really first saw a group of different academics, Bill Mollison, and David Holcomb doing research into permaculture in Tasmania, how could they actually generate a regenerative agricultural system, meaning that you could have perennial agriculture that didn't result in any agricultural waste that didn't result in sort of needing to retool the land, but that the nature could actually thrive as a result of the human interventions in that land. It extended itself into the realm of development over the course of really the the 90s. And I think the first person who really champion this concept was John Lyle, a professor at Cal Poly Pomona, who really developed this first book regenerative design for sustainable development that looked at the role that landscape could play in our cities to begin to enhance biodiversity. That begins to enable more of these ecosystem services to really thrive that as a result of development, we could actually do a better job of handling stormwater and improving health by integrating better natural systems versus relying on the great civil infrastructure that we've seen for decades now.

Pippa Shawley 19:35

It's interesting hearing Shawn talk about integrating those better natural systems because we talked about biomimicry in a previous episode. And you know, Janine Benyus often talks about how a city can mimic the forest next door and make it sort of indistinguishable. So it sounds like regenerative design is a way to make that happen. Yeah,

Colin Webster 20:00

in fact, we'll go on to hear what I think is a fantastic case study of regenerative design and practice. Shawn will talk about that soon. But I guess what you're picking up anyway is the fact that there's these great connections between regenerative design and biomimicry is literally made the reference to that. You're probably also hearing references to cradle to cradle on that whole mix as well. And of course, there are connections to circular economy, people will be hearing this and everything that Sean said so far. But I went on to ask him exactly where he thinks Circular Economy fits in all of this for him?

Sean Quinn 20:36

No, absolutely. I mean, I kind of look at the circuit time is having three key principles, the first principle to to conserve resources, second, to extend the life of those resources, and third, to regenerate nature. And I don't think that we need to start with any one of those, I think it's really critical, we start thinking about the circular economy is the open loop that we actually want to find the this we often talk about this linear cycle, and then a closed loop cycle. When we talk about regenerative design, we're actually recognizing that there is a flow of energy, both in natural systems, more finite systems, and as well as the influx of people and their relationships in development. And so this notion of trying to take a more circular path to construction, the way that we prepare a site, if we're going to do demolition, that we are able to capture as many, much of the resources within that, store it and reuse that whether it's directly tearing up the concrete of a road and feeding it back directly into other landscape materials, or as you've done in many projects, being able to use that as the aggregate for future concrete that reduces our resource use and consumption of, of our native resources. The material upcycling that we so well learned about in, in cradle to cradle and again, in upcycling by both Bill McDonough and Michael Brown guard is really critical to that sort of essence of not only creating like friendly materials, but like friendly materials that lasts. And so as we begin to look forward into construction, how are we designing better, for modularity for disassembly. And so that, number one, if we have to take down the building, we're able to deconstruct it, simply store those materials, for as much adaptive reuse as possible, or better yet, for us to retrofit those were rejected design, I think lends ourselves towards a greater opportunity. It's the essence of enhancing ecosystem services, by the relationship of that, so much of the built environment that we have, that it represents 3% of the total coverage of the earth sits idle, would be at our facades or rooftops, they're not actually doing anything than acting as a barrier, there's very little in nature that serves only that one singular function. And so as much as we can, when we are preparing a site, we often find contaminants under soil methodologies that we find based out of the role of permaculture are based on this concept of phyto remediation, we might be able to use poplars, willows, unique plant species that can actually initially do the processing of, of of all of those contaminants safely and effectively, and actually going to quite rapid rate. And so rather than encapsulating the toxins that we find it around, because of previous damage we've done, we can actually naturally process that those trees that grow can either be integrated fully into the development as is, or to be honest, they can be sustainably harvested. And that if you actually were to take down some of those trees to make way for future building, those materials can be utilized again into the future development, or into another portion of the design of of a building product. And so that's where we start seeing this role of not doing this continual damage, but actually continual mutualism, which initially is going to create balance. But it's when we start looking at those sort of idle spaces are rooftops and start thinking about the role that green rooms or blues might play, we begin to actually start creating systematic silos that exist beyond that of the sort of human interactions that that we have. So you

Colin Webster 24:28

see pepper them, there's so much in here that I really enjoy him. And what I liked from that sequence that we heard from Shawn was the talk of it, the rooftops and how at the moment, rooftops only really serve one purpose, but in nature, that's never the case. I think what I also find really inspiring was the use of the trees to soak up the contaminants to deal with them, and to use them as part of the construction or part of the site and then possibly part of the construction somewhere down the

Pippa Shawley 24:57

line. And what I also really like It was how he talked about designing with the future in mind and also the deconstruction as well as the construction because when we discussed biomimicry and we talked about helical blades, we said, they they mimic nature really well until it comes to the end of life where it isn't circular. But what Shawn's describing here is something that does sound more secular to me. Yeah,

Colin Webster 25:22

I think so. And he talked there about the three principles of the circular economy and how none of them come first. You better tell whoever formats our website or reports, I guess. But um, I like that point that there, there is no hierarchy there. Really. Right, we're gonna we're going to go on to talk about what I think is a fascinating case study. I've been telling lots of people in the office about this week ever since Sean told me about what's going on as US Coast Guard site. So listen up, you are going to be excited, can't wait

Sean Quinn 25:51

to give you one really concrete and very kind of, you know, a visual example of it, the US Coast Guard headquarters in Washington, DC. And this is where we were charged with actually being to manage the stormwater that came across this multi 100 acre site. And so there's an existing development at the top of the hill, we are both retrofitting and infilling, a building on the sort of lower side of the hill and their forest to our north and south, the water flows coming over that are going to inherently absorb toxins if developed as business as usual. And so the idea came about how do we actually look at the cascade of the buildings and actually create them through a series of intersecting rooftops landscape systems through green roofs, that began to be really sourced for the different soil species that we'd find in the mid Atlantic region and then the pea mat for us. By filtering through water and each of their layers of that rooftop, we remove every layer of toxin, we can be in to be able to introduce a diversity of plant species. And so that water cascades down these rooms and feeds into a series of different courtyards. So each courtyard actually is representative of an eco tone that you'd find in a different portion of the Mid Atlantic region, from the Appalachian Mountains all the way to the coast. And as water then flows out of that site, it feeds into a central we're more than 400,000 gallons, stormwater is managed in that process. It's funneled back through the building for non potable water use. And any of the water that actually filters beyond slowly feeds out to the Anacostia River, which is at present one of the most polluted water bodies in the mid Atlantic. But the water that leaves our site is more pure than the rainfall coming down to it.

Pippa Shawley 27:40

Let me get this straight. Colin, once the water has fallen from the sky, going through these courtyards, and come out of the coastguard site, it's cleaner than the water was when it fell from the sky. Is that right? That's

Colin Webster 27:52

right. And I mean, it sounds impossible. But he described the process there of how it all works. And that water as well as being potable water is no return to this river, which is filthy, as he says, but so they're actually in the process of cleaning that river thanks to the way they've built this building. Is

Pippa Shawley 28:11

it really cynical of me to be surprised by the fact that that sites can do that have that kind of positive effect on nature?

Colin Webster 28:18

I don't think it I don't think so because I felt the same way. And to me, it sounded a bit like sci fi, that promise that we've we've heard of a lot of times that we can add something positive to the natural environment and do better than nature is doing itself. And here is a living, breathing example of it. And it isn't just the water. So what is also happening there on these rooftops, his bald eagles are nesting on them. Deer are migrating across them. And they've planted 100 new trees, which are thriving, and they're sequestering lots of carbon at the same time. So there's a whole host of benefits there. And I guess

Pippa Shawley 28:57

going back to what Shawn was saying earlier about how we love to work in, like amongst the trees and things, turning up to work every day for the Coast Guards working there that must improve their way of life as well. You'd

Colin Webster 29:10

imagine. So given everything you said yes. And for those who are wondering about cost. There is a financial benefit

Pippa Shawley 29:17

here too. Okay, because I thought you were gonna say this was really expensive.

Colin Webster 29:21

No, no, well, it turns out the US Coast Guard would have been fined because they're responsible for managing the water that runs off this hillside. So they would have been fined if it was if it was dirty water, which would be typical, I guess, in a more typical setting. And so the direct financial benefit to the way they built the site to

Sean Quinn 29:41

and I think that's one of the most important things for us to look at is that while there might be an additional first cost, we start looking at a return on investment that happens within the first three to seven years, you generally can satisfy a typical developer. But the thing that I think we need to capture more of is what is the financial balance that have really supporting these aces of services, and that there is a other qualitative social benefit the people that live and work in those places, that they perform better, that they enjoy life better, that they explore and become more socially conscious about the environment. And then as we begin to do now on many other projects, we're starting to really measure the externalities, the carbon emissions of a project, and the cost that that has, all three of these projects actually ended up having a much better net carbon sequestration as a result of all of them, reinforcing the landscape systems around it. So

Colin Webster 30:41

Pepa, I hope my excitement about regenerative design was shared by you. Definitely. That's great to hear. I love I love the systems within systems approach, the regenerative design has where it doesn't just look at the building, but it looks at nature, it looks at the social benefits, too. And as I said earlier, more than any others of the schools of thought regenerative design has a very strong focus on community, which maybe in the recording there, we didn't touch on too much with Shawn. But it's all across the literature for anyone who's interested in learning more. Something

Pippa Shawley 31:15

that happens a lot in making this podcast for me is thinking, if I'd known about a lot of these things, when I was at school, maybe I would have become an architect or a scientist, and I think Sean's enthusiasm and like, focus on the interdisciplinary elements of this is really exciting. And I hope people are listening feel quite motivated by that. Yeah,

Colin Webster 31:37

definitely. I would hope so. So connections to Circular Economy, that's what we want to talk about. Right, exactly. So for me, I think it's very clear. The third principle, the circular economy, is to regenerate nature. And the whole purpose of the bio cycle is indeed to regenerate the biosphere. And that's a clear connection to John Lyle and regenerative design as a whole.

Pippa Shawley 32:01

And that's something that our colleagues at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation have really focused on this year, we're just bringing out a report called Building prosperity, which is looking at the link around built environment, the economic rationale for it and the links to the circular economy as well. So we'll put links in the show notes to that report. So that is regenerative design. Colin, what's next?

Colin Webster 32:24

Next up in the cities, we will look at industrial ecology. So please join us on that next episode. And if you've enjoyed this episode, as indeed Peppa and I have, then please share it with anyone who you think would be interested. And then come join us next week on the circular economy show.

Pippa Shawley 32:40

See you then.

The Circular Economy Show Podcast

The Circular Economy Show Podcast explores the many dimensions of what a circular economy means, and meets the people making it happen. Each week our hosts are joined by experts from across industry, governments and academia to learn more about how the circular economy is being developed and scaled.