Research shows that shoppers are ready for single-use packaging alternatives that will be at the heart of a circular economy for plastics.

Between 2019 and 2021, people altered their shopping habits to actively avoid plastic packaging, according to a study by consultancy GlobeScan. The statistics can serve as a catalyst to businesses exploring packaging innovations, indicating that people are motivated to change their buying behaviour in order to eliminate plastic waste.

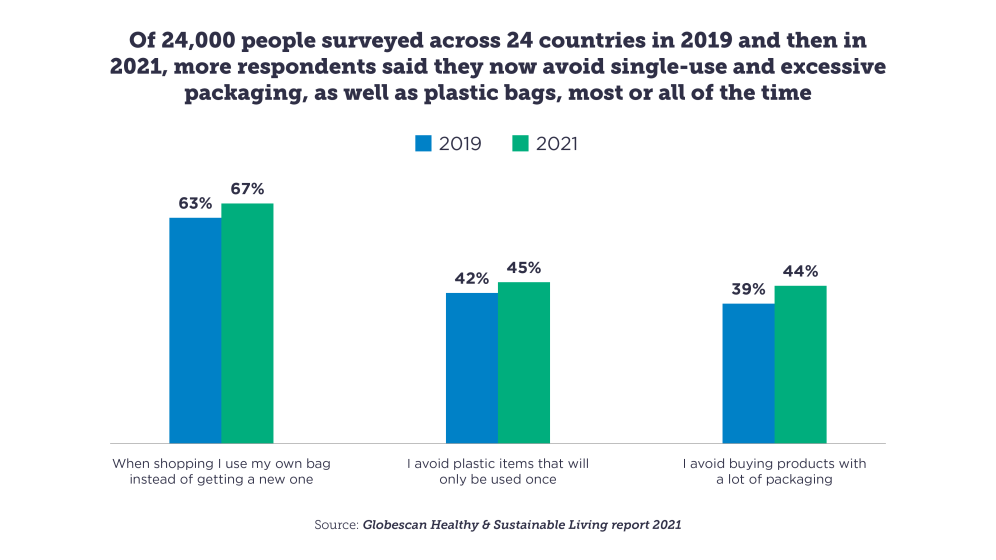

The Healthy & Sustainable Living survey asked 24,000 people across 24 countries over the summer of 2021 about the variety of ways they try to minimise waste and environmental impact in the way they shop. 44% said they avoided buying products with ‘a lot’ of packaging ‘most’ or ‘all’ of the time, up from 39% when the survey was conducted in 2019.

This is mirrored by rises in the avoidance of plastic shopping bags, and single-use plastic items in general, and represents a significant shift in reported behaviour over a relatively short period.

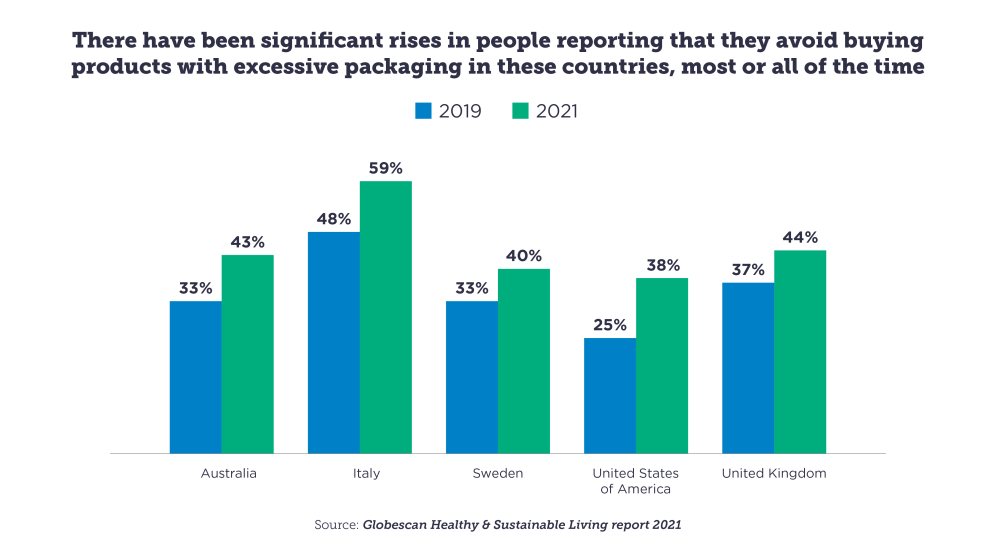

The increase in plastic packaging avoidance is most marked in the US, where 38% of Americans in 2021 said they rejected products that they regarded as having a lot of packaging. Although this is less than the global average it is still a significant rise on the 25% who said the same in 2019.

The most enthusiastic plastic packaging avoiders were those from China and Italy with 59% of people surveyed saying they rejected products with a lot of packaging ‘most’ or ‘all’ of the time. It may be that this figure is elevated in these countries because food is available unpackaged more often than in some other countries. In China in particular, the rise in popularity of community-supported agriculture can be viewed as accelerating this trend.

In the UK, 44% of shoppers said they rejected excessive plastic packaging, while 47% of those in France said the same.

The data also echoes other research that has shown growing public concern about plastic packaging. A survey of 2,518 Australians in 2018 found that nearly a quarter (23.2%) of shoppers take action to reduce their use of plastic packaging at least 70% of the time.

Meanwhile, in the UK, research among 1,000 adults by Delineate the same year found 53% of shoppers ‘always or mostly’ buying groceries that come without plastic packaging and WRAP research noted 68% of people as saying they had become more concerned about plastic packaging waste over the previous year. Cutting out packaging from fruit and vegetables was found to be shoppers’ most favoured route to reduce plastic packaging in a YouGov study in 2019. 81% of UK consumers said they were trying to buy less of these products if they were surrounded by plastic packaging. Household cleaning products were the next most popular segment in which they were trying to minimise packaging.

It’s worth noting a caveat to these data sets. The concept of ‘a lot’ of packaging, for example, is subjective, and research subjects can often be positively biased in favour of their own behaviour. But the fact that numbers of people reporting that they avoid excessive plastic packaging are on the rise indicates a growing motivation to act, according to Tove Malmqvist, Globescan senior project manager.

Covid has changed the way we shop

Given the change in buying behaviour highlighted over two years by the Globescan study, it is reasonable to assume some degree of impact resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, as the timing has coincided. Exactly how successive lockdowns and the prevailing public narrative about health may have accelerated public motivation to shop differently requires specific research. Some had even speculated that users would become more tolerant of plastic packaging if it aided infection control. But one possibility is that the increase in single-use plastics generated as a direct result of the pandemic has motivated end users to make changes where they can.

A report from the OECD refers to the weight of single-use plastics in personal protection equipment (PPE) like masks and gloves, as well as the rise in plastic packaging generated by all the extra e-commerce deliveries over the past two years. Restaurants switching operations to home deliveries also led to extra plastic packaging. One small-scale survey during the first lockdown discovered that households were generating 30% more plastic waste than pre-covid as people were relying on more online supermarket orders with packaged fruit and vegetables.

It may be that once they were able to shop in person again, citizens have been voting with their wallets to reject over-packaged items. The fact that reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification. platformLoop steadily built distribution over the same period also supports this theory. It also became clear that food shoppers were keener on sourcing their produce direct from specialist butchers, greengrocers and bakers in some countries.

This is a trend that could have been influenced by a variety of social and environmental factors. However, research has certainly indicated that, contrary to concerns in the early months of the pandemic, Covid has served to increase environmental awareness.A study of 3,000 people in eight countries by consultancy group BCG (July 2020) found 70% saying that they were more aware than before the pandemic that human behaviour threatens climate, and that environmental degradation threatens humans. A resounding 87% across all the countries in the poll thought that private companies should integrate environmental considerations into their products and the way they operate, either ‘a lot’ or ‘somewhat more’.

A circular economy for plastics is the system change that delivers user needs

A growing public appetite to avoid waste is one element that will help facilitate the movement towards a circular economy for plastics. This aims for complete system change based on three principles: eliminating the plastics we don’t need; innovating to ensure that the plastics we do need are reusable, recyclable, or compostable; and circulating everything we use. The net effect is that the value of materials is constantly maximised, rather than wasted, as is the case in the current, linear economylinear economyAn economy in which finite resources are extracted to make products that are used - generally not to their full potential - and then thrown away ('take-make-waste')..

Bringing about complete system change isn’t a small task. But for companies keen to embrace this thinking, the place to start is upstream innovation - reimagining a product, packaging or business model to design out waste in the first place. Downstream innovations like recycling are still necessary, but it is the upstream efforts that are likely to deliver the widest-reaching changes.

Some companies with heavy current investments in plastic packaging have already been moving towards this vision, exploring upstream innovation alternatives like reusable packaging, refill systems, and new product/packaging formats. The latter has attracted a variety of innovations from start-ups, including Apeel and Mori, edible coatings for fruit and vegetables that avoid altogether the need for any single-use plastic wrapping.

The New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, led by The Ellen MacArthur Foundation and UNEP, provides a benchmark of this activity by measuring the efforts of businesses, which together represent over 20% of the plastic packaging market, as well as governments to realise a vision for a circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. for plastics.

In 2021, signatories’ progress showed that, although brands’ and retailers’ use of virgin plastic has peaked and there has been action on recycling, there have been limited attempts to introduce reusable packaging at scale. Reuse is an effective way to design out single-use plastic packaging, but companies are not yet prioritising innovations or infrastructure development in this area at sufficient scale.

Less than 2% of Global Commitment signatories’ plastic packaging was reusable, as reported in 2021, and more than half of all signatories reported that they use no reusable plastic packaging at all. While developing reuse options takes time, more concerning is that levels of ambition to explore and scale reuse appear low. Just 11% of signatories launched more than three pilots during 2020, while 56% launched none at all.

But we may be on the cusp of change. In early 2022, Coca-Cola published a plan to make 25% of its packaging reusable by 2030 – the first major FMCG manufacturer to set such a target. PepsiCo indicated that it also intends to set a reuse target in 2022.

Unearthing barriers to progress in this area is complex. There are a variety of logistical, economic, and communications issues that will require collaboration by a variety of industry players to arrive at a solution.

User demand can never be the pivotal action on this issue. The creation of a circular economy for plastics must involve all parties in the complex plastics system taking their active part, including businesses, governments, and NGOs, as well as shoppers.

Plastic pollution is rapidly outpacing current policy efforts to stop it. Existing regulations are often limited to banning or taxing very few specific single-use items, such as plastic bags, or focus exclusively on improving waste management and packaging recycling while ignoring the need for upstream interventions.

But in Europe at least, there are two new policy initiatives that could represent the start of effective systems change. France has required retailers to sell most fruit and vegetables without plastic wrapping from the start of this year. On a wider scale, the United Nations Environment Assembly agreed to start negotiations on an international legally-binding treaty this year that aims to reduce plastic pollution along the full life cycle of plastic products and packaging, including through a circular economy approach.

Businesses and governments need to work together to establish the commercial models and regulatory frameworks that will make reuse a viable on-going part of a circular economy for plastics. The task to build on shoppers’ concern with plastic packaging and actually alter their shopping habits can happen within this context.

Influencing buyer behaviour

Judicious use of public policy can nudge changes in consumer behaviour. It was only a few years ago that it was normal to see a sea of plastic bags covering the end of every checkout in a supermarket. Growing public awareness of plastic pollution and, in the UK, a simple financial levy persuaded people to remember to bring their own bag with them. 67% of shoppers globally now take their own bag with them to the supermarket, according to Globescan’s research, rather than getting one at the checkout.

Part of the behavioural task now is to take this change a step further – asking users to remember to bring appropriate reusable containers with them to stores as well as bags.

Some early pilots have shown that the use of reusable containers can be even simpler, via a refill at home model facilitated by digital technology, with more convenience for users as they don’t have to remember something else as they head out shopping. Chilean social enterprise Algramo delivers laundry liquid to people’s doors by tricycle in response to a request processed by an app. Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tagged containers are given to them at the first order and then the user just has to bring them out to their doorstep each time to fill up. This system worked well during the pandemic when people were particularly keen to avoid stores.

Food and cleaning products giant Unilever has also been exploring the issue of reuse, with pilots (each in conjunction with a local retailer) set up in Australia, Pakistan, Mexico, and the UK. In the UK, it has extended its tests of refillable bottles of brands including detergent brands Persil and Radox in Asda stores.

These pilots have made clear that it will be essential to come up with an offer that not only gives shoppers the buzz of avoiding wasteful packaging, but that also works for them on price and convenience too. A circular economy ultimately offers the prize of reductions in material costs as a result of more effective systems. In the transition period however, in order to keep prices to end users at a level that invites them to experiment with reuse, companies will need to regard the costs of early innovation pilots as investments in future strategy.

Part of the evaluation of these pilot projects is working out the right reuse model for different products and markets. There are four reuse categories: refill at home (as in the Algramo example); refill on the go (including in-store, as in the Unilever trials); return (of a container) at home; or return on the go.

Coca-Cola Latin America has spent the past few years refining a reuse project that fits in the fourth category, and potentially offers the kind of reuse model that users could easily understand their role in.

The company created a standardised PET bottle in 2018 that Brazilians can bring back to stores in return for a discount on their next purchase. Bottles are returned to the bottling plant, where they are washed, refilled, and relabelled. Return rates are around 90%, and this programme has effectively taken 200 million bottles out of landfill.

The Universal bottle project has now been rolled out into seven countries across South and Latin America and forms part of the drinks giant’s efforts on reuse.

This type of deposit-return model has also been adopted by Starbucks and McDonald’s. Both are currently trialling schemes that offer customers the option to pay a small deposit to borrow a reusable cup in return for a small discount on the cost of their drink.

Reuse as a branding opportunity

Communications will be key to helping users understand the logistics and advantages of the various packaging reuse models on offer. At the moment, refilling at home has proved the most popular reuse model in the UK, according to a study by the Institute of Grocery Distribution (IGD), with return on the go and return from home also showing potential.

The IGD study also discovered that 41% of people had already used some form of reusable packaging, and flagged the value of using loyalty points to motivate more users to make the switch in habits.

There is a big opportunity for any FMCG or retailer that makes a move into this space to align their brand with the push to rid the world of plastic packaging via reuse.

Reusable product maker Chilly’s hit the headlines in June 2022 with a poster campaign urging bottled water brands to offer reusable bottles. It teamed up with reuse charity City to Sea for the campaign, which also involved a letter signed by over 400 other groups, calling on FMCG giants Unilever, Nestle, Procter & Gamble, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola to commit to viable reuse and refill systems.

Ecover has been banging the drum for refills since 1989 – it fits well with the brand’s eco-conscious positioning. Over 700 refill points in independent shops across the UK are promoted on City to Sea’s Refill app, and more recently it has created refill pilots within a few Sainsbury’s stores.

As part of what it calls its ‘Refillution’ campaign, Ecover’s head of long-term innovation Tom Domen published a report containing the company’s learnings on reuse, intended as an encouragement to other brands’ efforts.

The report makes five recommendations for increasing shoppers’ motivation to refill: leverage novelty; create objects (containers) of desire; highlight advantages of reuse; create a movement; and give ways to save money.

On the subject of the logistics and the business case for refills, there are five more tips: remove the refill premium (i.e. extend refills to more mainstream brands); de-risk the process; design for minimum agency; design for the fail case; and meet shoppers where they are.

Marketers have historically been cautious about introducing product and packaging developments that users are not ready for. But that era has passed – shoppers are clearly waiting for companies to bring innovations to the market to catch up with the way they would now like to shop. They are also starting to get more actively involved – 175,000 UK households took part in Greenpeace’s Big Plastic Count in May to discover exactly how much plastic packaging is thrown away.

A significant communications campaign to launch a reuse system could easily tap into the significant latent user desire to make a contribution on this subject – a survey of 2,000 UK shoppers (IGD) released at the end of 2021 found that 78% of people felt that more big brands should offer the facility to refill/reuse their packaging.

Although this is only UK data, it does underline the spirit of the Globescan research – a global audience of shoppers increasingly keen to be offered alternatives to single-use plastic packaging.

But, as the brands and retailers taking part in the pilot projects have discovered, getting the price and logistical offer right for users is crucial. Many Zero Waste shops have experienced a dip in revenues since the start of the pandemic, with owners reporting that shoppers could no longer afford the price premium or the time involved in making a trip to another store. It may be that (as the IGD has indicated) reuse models that meet users where they already are – whether at home or within supermarkets – will prove most viable.

Despite all the practical and financial challenges that system change presents, a transition to a circular economy for plastics delivers a way for companies to carve themselves out an authentic brand positioning as progressive and socially-conscious. But this must be underpinned by demonstrable, scaled action to provide users with viable alternatives to peeling vast amounts of plastic packaging from their shopping.